Calculus in Medicine

When I

thought of calculus, I used to think of maths. And physics. And engineering.

Which is why I found these lines in Steven Strogatz’s Infinite

Powers

very, very surprising:

“Consider the

surprising role that differentials (calculus) played in the understanding and

treatment of HIV.”

Back

then, it was known that HIV went through 3 stages:

1) In the first stage, an infected

person has flu-like symptoms;

2) Next, a 10-year period of no

symptoms;

3) And finally, AIDS sets in,

weakening the immune system to a point where other infections overwhelm the

system and kill the patient.

Tests

had shown that the number of virus particles in the bloodstream was high in the

first stage (hence the symptoms); was low but not gone altogether (the “set

point”) in the second stage; and was overwhelming in the last stage.

With no

cure in sight, all kinds of ideas were tried. One such team was of Dr. David Ho

and Alan Perelson. The former was a former physics major, and the latter was a

mathematical immunologist. Note how both had a maths background and were

probably guys “comfortable with calculus”, writes Strogatz.

In

1995, the team gave patients a protease inhibitor as a probe, not as a treatment. This moved the “set

point” and allowed them to “track the dynamics of the immune system as it

battled HIV”:

“The rate of decay

was incredible; half of all the virus particles in the bloodstream were cleared

by the immune system every two days.”

This

was an exponential decay, exactly the kind of stuff that calculus is used for.

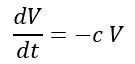

Ergo, the two realized if V = concentration of the virus, then:

That’s

maths-speak for saying that the rate of change of V (virus concentration) is a

function of the virus concentration itself. The negative sign signifies a

decrease.

Solving

the equation, they realized that the supposedly “dormant” 10-year period was

anything but. Instead, it was a period of pitched battle where the two sides

were dead-locked:

“The immune system

was in a furious, all-out war with the virus and fighting it to a near

standstill.”

The

casualty count in this standstill was staggering: a “billion virus particles” were being killed every day in this supposedly dormant phase. Obviously, the same

billion were also being replaced every

day, hence the deadlock.

The

researchers then collected data right after the protease inhibitor was

injected: “every two hours until the sixth hour, then every six hours until day

two, and then once a day until day seven”. They also adjusted for other aspects

not factored in the first time around. The numbers this time were even more

stunning:

“Ten billion virus particles were being

produced and then cleared from the bloodstream every day.”

Moreover,

they also found that the lifespan of the infected cells was only two days. That short life cycle would

also a prove key learning.

So how

did all this help fight HIV/AIDS? Until then, doctors prescribed anti-viral

drugs only after, not during, the 10-year supposedly hibernation

period. Why? It wasn’t doing any harm until then, they reasoned, and besides,

hit it too early and it would inevitably mutate and become immune to those

drugs by the time you really needed them.

Ho and

Perelson’s work upended the entire approach to treatment:

1) It showed there what was thought

of as a hibernation period was really a period of pitched battle every second, every day;

2) It was clear that the key was to

help the immune system in that 10-year period when it was still functioning.

Conversely, the last stage was the period where the virus had the upper hand.

Reinforcements then were too little, too late;

3) It also explained why no single

medication ever worked:

“The virus replicated so rapidly

and mutated so quickly, it could find a way to escape almost any therapeutic

drug.”

But

wait, the duo wasn’t done yet. Perelson proved mathematically why no one drug

stood a chance:

“By taking into

account the measured mutation rate of HIV, the size of its genome, and the

newly estimated number of virus particles that were produced daily, he

demonstrated mathematically that HIV was generating every possible mutation at

every base of its genome many times a day.”

He went

on to prove that a two drug-combo wasn’t good enough either, but a three-drug

combo had a ten million to one odds of success.

And

that is why HIV has been a triple-combination therapy ever since. But even that

combo doesn’t eradicate the virus altogether. Yes, their numbers become undetectable

within two weeks, but they are there nonetheless. And they rebound if the

medication stops. That’s why HIV-positive people need to keep taking their meds

lifelong: it’s a chronic condition.

A

chronic condition is still a huge improvement over the pre-calculus analysis

days outcome of inevitable death, so let’s treat this as a win.

Comments

Post a Comment