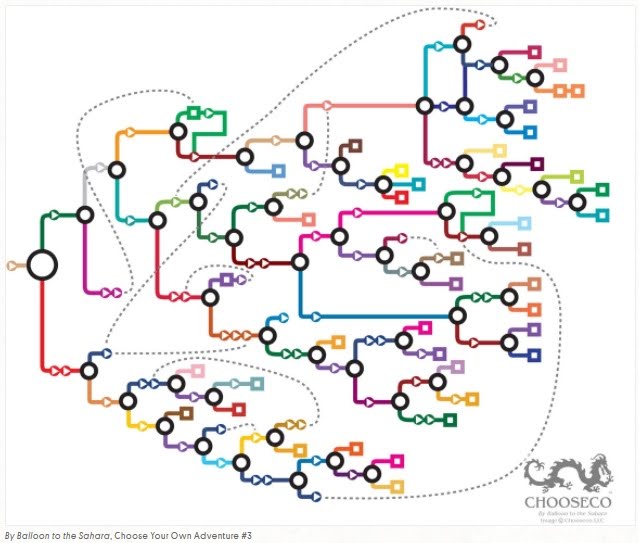

Map to Read a Book!

As a teenager, I read a few Hardy Boys books where at the end of some pages, you’d have a choice: If you want to pursue the crook, go to Page 30. If you want to take the victim to the hospital, go to Page 40. It was interesting at times, and choices at some points may lead you back to pages you had already visited via a different series of choices. But I had never read (nor even knew about) a similar category called the “Choose Your Own Adventure” book. It too had the same forks where the reader makes choices to decide which page to read next. So what was the difference of this new kind from the type I had read? In the kind I had read, the final outcome was guaranteed: the good guys would win, the crooks would end up behind bars. Only the path to that outcome would vary. Whereas the other kind could have different “types of outcomes at the end of each path”, writes Sarah Laskow . The endings cover the entire spectrum from “great, favorable, mediocre, disappointing, or catastrop