Coronavirus: Do Lockdowns Work?

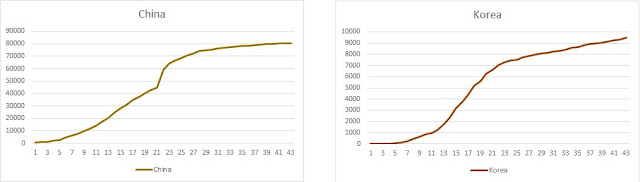

In my last blog , I asked if we should look East, i.e., at how China, Japan and South Korea are dealing with coronavirus. Since those countries got hit first (whereas Europe and the US got hit later), there’s data for a far longer period from the 3 Asian countries compared to the West. To adjust for that, I’ve taken the total cases count for the first 43 days in each country (that corresponds to present day for most of the West). First up, China and South Korea: Don’t worry about the exact numbers. Look only at the shape of the curve for both countries: a slow rise (few new cases per day), that changes to a steep rise (lots of new cases per day), and by Day 25 or so, both countries managed to flatten the curve (back to few new cases per day). In other words, Day 25 corresponds to the time when the effects of their lockdowns began to show up. Next, look at Europe and the US for the same period (first 43 days): The curve starts picking up much later (there’s the ges