Apps for Age Groups?

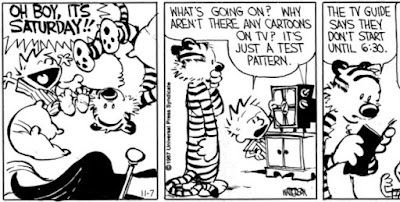

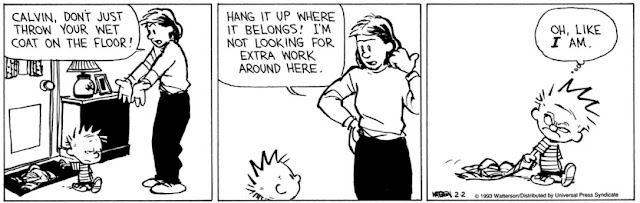

As someone who can appreciate good photography and art, I love Instagram (Yes, there’s a lot more to it than just pics of whatever people are eating). Every now and then, I’d show some really nice pics on the app to my 8 yo daughter. And since there is literally an endless stream of pics the app shows you, she’d then immerse herself of what is called “infinite scroll”, scrolling without end. Then one day, when I showed her yet another pic on the app, here is the conversation we had: She: “Isn’t this app for young people?” Me (wondering how she even knows such things): “Yes, what’s your point?” She: “Aren’t you too old for it then?”, adding pointedly, “Just as you say I’m too young for some things?” Me: “No, I’m not too old for it.” She: “Really? Aren’t you forty-whatever?” Forty-whatever? This from the same kid who gets mad when I can’t remember how old she is… FYI, kiddo, I don’t even remotely subscribe to the view expressed in this rant by an “adult”, Ni