Tax on Sin

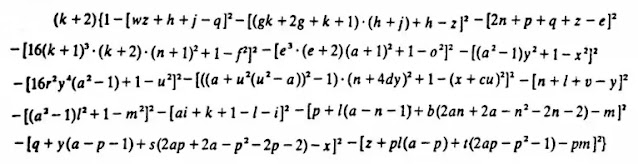

Online gaming and gambling in India got hit with a 28% GST tax. This was a huge increase, by a factor of 10-11 times . In theory, this means additional government revenue of ₹20,000 crores annually. (In practice, who can say? Maybe demand and supply will change due to the new tax rate. Maybe some of it will go “underground”, i.e., be done illegally). Is this any different from other “sin taxes”, like the high tax rates on alcohol and tobacco? Not really. The question though is what is the purpose of sin taxes – to reduce consumption of something “bad”? Or for the government (and thus the country) to collect money that could be spent on other things? Historical data suggests that if the aim is to reduce consumption, it doesn’t make much of a difference (Yes, cigarette consumption has reduced as taxes increased, but that’s because of the growth in awareness of the link between tobacco and cancer). This blog asks an interesting question - what should be considered a “sin good