Shapes of Letters

Is there any pattern to the letters across written languages, asks Stanislas Dehaene in Reading in the Brain. At first sight, it seems like an idiotic question: the Roman, Arabic, Devanagari and Chinese scripts hardly resemble each other in any way. But look at things a little differently, and a pattern emerges.

Perhaps, one

hypothesis goes, certain letter-like shapes are omnipresent in what we see

around ourselves. For example:

The frequency of these shapes is even higher if rotated shapes are counted as the same shape:

If you felt that

rotating the shapes and still thinking of them as the same letter is cheating,

think again: our brain adjusts for orientations – how else would it recognize

the same object again, when it is viewed from a different angle?

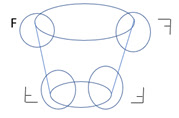

Next, consider

these drawings, where the same shape is drawn with varying degrees of

completeness:

Notice how the

middle column is almost interpretable whereas the first column isn’t? Why is

that? The difference between the two is that the second column includes the

junctions, the meeting point of two surfaces.

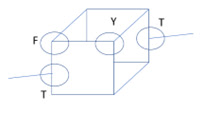

Now look back at

the first picture at the top. The F, T and Y shapes are junction shapes –

perhaps this is why our brains evolved to recognize those letter-like shapes,

says the hypothesis.

But, you counter,

the F, T and Y shapes are Roman characters. We don’t find them in the other

scripts. Doesn’t that prove this hypothesis can’t be a universal reason

for character shapes?

Marc Changizi

answered that question. Two lines can intersect to form only 3 letter shapes:

L, T and X. Three lines can intersect in far more ways: F, K, Y, Δ etc. He then

looked for the frequency of these shapes in various scripts… while ignoring

their orientation, i.e., a tilted (or mirror-image) F still counted as an

F. Guess what he found? Across all scripts, the L and T shapes occurred the

most, X and F were next, and so on. These patterns were the same across

scripts.

In fact, the

frequency of occurrences of these shapes in the scripts matches the frequency

of occurrence of these shapes in natural objects. This then is why many believe

the following:

“Our

primate brain only accepts a limited set of written shapes.”

And:

“We

did not invent most of our letter shapes: they lay dormant in our brains for

millions of years, and were rediscovered when our species invented writing the

alphabet.”

It sounds like an interesting hypothesis.

Comments

Post a Comment