Middle-Class and Meritocracy

In her

terrific book on (middle-class) parenting, All

Joy and No Fun,

Jennifer Senior has a chapter on how (over)involved parents are in their kids’

activities. Apparently, there’s even a term for it: “overscheduled kids”! It

refers to all those play dates and extracurricular activities, almost “as if

(kids had) all suddenly acquired chiefs of staffs”. And the term for this

aspect of parenting? It’s called “concerted cultivation”.

Most

Indians can relate to all this, but it’s bit surprising that the same is

increasingly true of American middle-class parents as well. In fact, in the US,

there’s an increasing backlash now against (hold your breath) meritocracy! Huh?

Joan

Wong put together 10 academics’ take on what this

is all about. One panelist, Agnes Callard, makes an interesting point on two

types of merit: “(backward-looking) honor and as a (forward-looking) office”.

Most people are OK with the first, it’s the second one, the future-looking one

(aka college admission) that is the bone of contention.

But

why? After all, the kid who got the most marks got into the best college,

what’s wrong with that? Daniel Markovits counters with an argument most Indians

have long been familiar with:

“The United States

has one of the steepest educational hierarchies in the world. Not just colleges

and universities, but also high schools, elementary schools, and even

preschools all come in shades of eliteness. At every level, elite schools

invest much more in training their students than their ordinary counterparts.”

And:

“Children of rich

and well-educated parents imbibe massive, sustained, planned, and practiced investments

in education from birth through adulthood.”

You’d

think that, in the US, where everyone goes to the neighborhood school, this

shouldn’t be an issue. Wrong. Everyone tries to move into the neighborhood with

the best schools, which drives up real estate prices, and that then means only

those with more money go to the best schools.

On top

of that choice of school, Caitlin Zaloom points out the well-off then add even

more advantages for their kids:

“Glowing

applications are not merely produced by good grades; they’re largely the result

of test tutors…”

And

that’s the gist of the argument against meritocracy: Those who couldn’t afford

all this initial investment don’t stand a chance. The opportunities aren’t

equal, so the outcome is guaranteed to be skewed. The kids whose parents can

afford/provide the opportunities will always win the race. Or as Thomas Chatterton

Williams says:

“Is this — the

presence of an engaged parent who values education — itself a form of privilege

and therefore unmeritocratic? Some would say yes.”

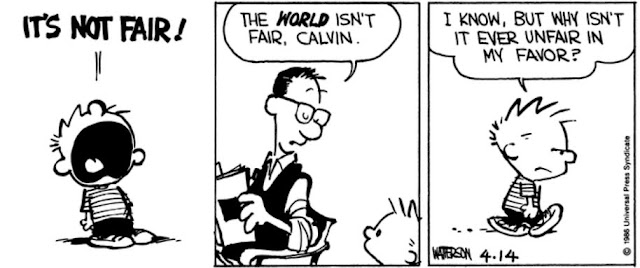

All

this reminds of this Calvin and Hobbes

strip:

The

middle-class has found something that is “unfair in my favor”, and so meritocracy

ends up being the way Williams describes it:

“But life is

neither perfectible nor equalizable, and success through competition — even

success derived from grit, hard work, and merit — is often intergenerational.”

And,

let’s face it, there’s really no choice in this rat race, as Senior wrote in

her book:

“It’s the

problematic psychology of an arms race: the participants would love not to

play, but not playing, in their minds, is the same as falling behind.”

Fair or

not, I don’t see how anything can change on this front…

Comments

Post a Comment