Braille and Computer Science

Code is a book that I wish I had read in college. At one point, Charles Petzold explains the Braille system used by the blind and (beat this) how relevant it is to modern day computers! (Actually, I am not sure if that’s because computer science/communication ideas flowed back into Braille; or the other way around).

Louis Braille was

French, went blind at the age of 3 in the year 1812 and “would have been doomed

to a life of ignorance and poverty” (There was no system of reading for the

blind back then). The closest system arose in 1819 via a captain of the French

army, Charles Barbier. Called “night writing”, it was a pattern of raised dots

and dashes meant for soldiers to communicate at night, without giving away

their positions by lighting candles. But it was too complex a system for the

blind to use, at best OK for short messages, but not scalable to entire books.

Braille took that system and tailored it for the blind.

Now to the

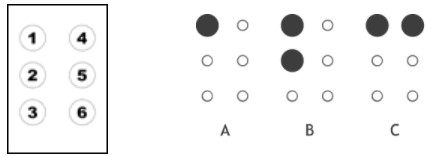

relevance of that code to modern day computers. Braille is a 3X2 (3 rows, 2

columns) grid of dots. Each combo of raised and lowered dots in that grid

represents a different letter or number or whatever.

Notice the

similarity to computer codes yet? Each dot can be raised or lowered: 1 or 0.

Each dot of the 3X2 grid is a binary digit (bit) in other words. A combo of

these bits represents a letter!

But if this was

all there is to Braille, we could have just talked of Morse code (dashes and

dots can be considered a form of binary too). If you do the maths, Braille

allows for 2 X 2… X 2 (6 times since there are 6 slots) permutations, i.e., 64

possible characters.

English needed 26

+ 10 = 36 characters. But the nearest power of 2 that supports 36 is 6 dots (5

dots would allow support 32 possibilities). Even if French has a few more

letters, surely 64 is overkill. The rest must be unused, right?

Wrong. If you have

the extra slots available beyond letters and digits, why not use them for other

things? Like punctuation marks. Sure, but even after that, you’re left with

many unused codes. The Braille code over time started assigning those unused

codes to:

- Common words like, in English, “the”, “of”, “for”, “but”, “is” etc;

- Common letters that occur in succession e.g. “ch”, “th”, “ou”, “er” etc;

Makes sense,

right?

But even after all

of the above, we’re still left with several unused codes. Today, many are used

as “precedence” or “shift” codes, i.e., “they “alter the meaning” of how to

read the code(s) that follows. For example, one precedence code basically says

“Consider every code that follows to be a capital letter”, until told

otherwise. Which, of course, means that there’s a code for “End of

precedence/shift” interpretation.

Obviously,

different languages assign different codes for characters unique to their

language. In other words, the same Braille code can stand for different things

in different languages. See the parallel to how files on your computer, all

with 1’s and 0’s, can be interpreted as a text file or a video file?

Like I said at the top, I don’t know how many of these ideas have flown back from computers/communication fields back to Braille over time. Regardless, the concepts today in both are the same on multiple fronts. And it’s a lot easier to understand it starting from Braille than it is to understand the same starting from the computer/communication end. Perhaps they should teach it from the Braille end at computer science and communication courses at college…

Comments

Post a Comment