From Wind to Steam Powered Ships

Back in the days before steam began to power ships, they were all wind powered. That, by definition, meant the trip was entirely dependent on the winds. In A Splendid Exchange, William Bernstein brings out two such instances. The first one was the route from the Middle East to India:

“The seasonal dance of the

monsoons – southwest in summer, northeast in winter – would dictate the annual

rhythm of trade in the Indian Ocean.”

The second instance

is brought out in the problem for a trip from Portugal to the bottom of Africa

by trying to hug the curve of the African coastline:

“South of the equator, as

southerly trade winds increasingly blew against

his ships, progress became ever more difficult.”

This was such a

big pain that Vasco da Gama was willing to experiment with an alternative

route, even one as long winded as this:

“(As they passed Sierra

Leone), they turned right, departed the coast for the open Atlantic… Then the

ships gradually executed a counter-clockwise semicircle thousands of miles

wide, enabling them to tack across the wind blowing directly on their port

sides.”

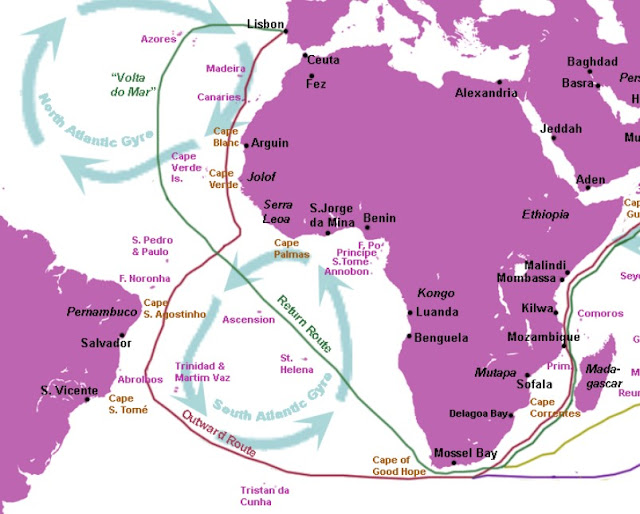

The arc was so “generous” that Da Gama’s fleet “came within several hundred miles of Brazil”! If that’s hard to visualize, see the red line in the map below:

With all that in

mind, you’d think the advent of steam would mean a rapid transfer of all sea

traffic from wind to steam. Bernstein explains why the speed of transfer was in

fact far, far slower.

To generate steam

power, coal had to be burnt. That coal would have to be carried in the ship

itself, thereby reducing the amount of goods that could be carried in the ship,

in turn increasing the transportation cost per item. Another issue was that a

steamship cost 50% more. Plus, a steamship needed larger crews, 50% more. A

steamship couldn’t be built of wood (what if the coal lit up the wood?!), and

metal hulls required a lot of maintenance to prevent rusting and to deal with

the corrosive effect of sea water.

To sum it up,

there was a particular distance above which wind was the better option.

Initially this number was low, and so wind ships thrived. With technological

advances and operational efficiencies, the number increased thereby reducing

the routes for which wind still made sense. But that was a slow process. What

really tipped the scales to steam was the opening of the Suez Canal, reducing

the distance from London to Bombay from 11,500 to 6,200 miles. Even worse, wind

ships could not sail up the Red Sea against

the wind. The opening of the Panama Canal ended matters: there were no

routes left anymore that were so long that wind made sense.

It’s all so very fascinating.

Comments

Post a Comment