Knowledge and the Tripartite Account

What does it mean to know something? More specifically, what does a person mean when he says that he has knowledge of something?

In science, the answer to that question involves 3 parts (the Tripartite Account):

1) Belief: You should believe what you claim to know. After all, if you don’t even believe it yourself, how can you say you know it?

2) Justification: You should have valid reasons for your belief.

3) Truth: What you claim to know should, in fact, be true.

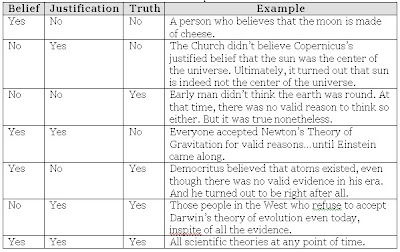

This seems very tame and oh-so-obvious at first. Until you consider cases that violate one or more of the items of this Tripartite Account:

So the Tripartite Account sounds like a good way of defining knowledge, right? Unfortunately, no. There is a whole class of counter-examples called Gettier counter-examples that shows the inadequacy of these 3 conditions. Here’s an example: it’s afternoon, you look at your watch and it says 3 o’clock. So you believe it is 3 with valid reason (your watch says so) and let’s say it is indeed 3 PM. So far so good, but what if your watch had stopped working and has been showing 3 PM regardless of what time it is?

You met the Tripartite Account conditions, but surely you can’t say you know it is 3 PM? And so the hunt is on for that 4th condition to add to the Tripartite Account conditions to define what it means to “know” something. Who knew that defining what it means to know could be this hard!

In science, the answer to that question involves 3 parts (the Tripartite Account):

1) Belief: You should believe what you claim to know. After all, if you don’t even believe it yourself, how can you say you know it?

2) Justification: You should have valid reasons for your belief.

3) Truth: What you claim to know should, in fact, be true.

This seems very tame and oh-so-obvious at first. Until you consider cases that violate one or more of the items of this Tripartite Account:

So the Tripartite Account sounds like a good way of defining knowledge, right? Unfortunately, no. There is a whole class of counter-examples called Gettier counter-examples that shows the inadequacy of these 3 conditions. Here’s an example: it’s afternoon, you look at your watch and it says 3 o’clock. So you believe it is 3 with valid reason (your watch says so) and let’s say it is indeed 3 PM. So far so good, but what if your watch had stopped working and has been showing 3 PM regardless of what time it is?

You met the Tripartite Account conditions, but surely you can’t say you know it is 3 PM? And so the hunt is on for that 4th condition to add to the Tripartite Account conditions to define what it means to “know” something. Who knew that defining what it means to know could be this hard!

The last example shown in the table for the 'Yes, Yes, Yes'combination is not up to the mark.

ReplyDeleteAn inherent contradiction to this example crops up immediately, straight from the previous example for 'Yes, Yes, No'which cites Newtons law of gravitation. Since such a condition may arise for any scientific 'belief'- irrespective of the 'justification'-, it may just not be possible to give a true example for the 'Yes, Yes, Yes' situation at all! Making the yes-yes-yes example conditional (using qualifiers such as "at a point in time") leads to the fundamental philosophical question, "Is is really possible to give a valid, timeless and non-trivial example for the yes-yes-yes scenario?"

I suppose your elaboration of how the time piece (indicating wrong time) defeats the boundaries of the analysis presented supplements the above argument.

These apart, is there any real use for such categories and the analysis by applying them?